Exhibition Profile | An Urban Atmosphere

JOSEPHINE KELLIHER REFLECTS ON THE PRACTICE OF MICHAEL KANE.

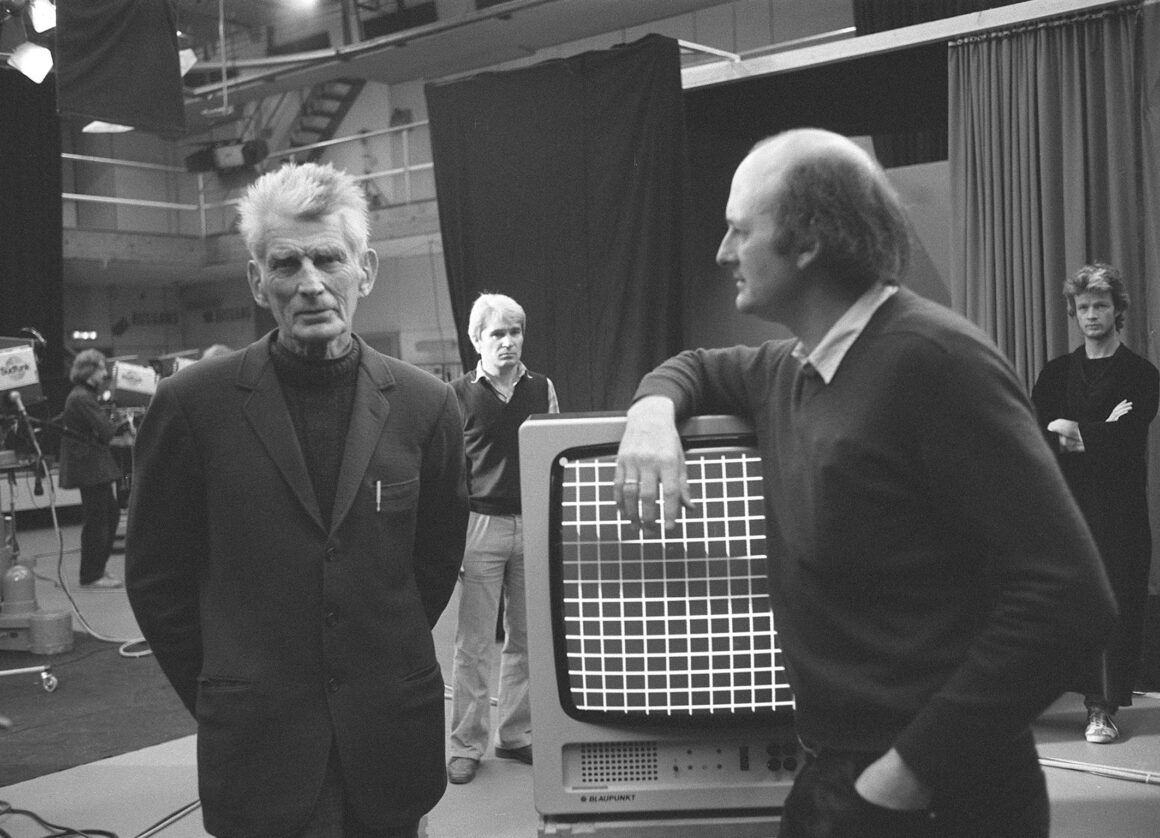

Michael Kane was among the first artists to join the fledgling Rubicon Gallery in 1990. We worked together intensively for 25 years and continue to collaborate. Michael’s exhibition ‘Works on Paper’ at Taylor Galleries (22 May – 21 June) coincides with his 90th birthday, so this is an ideal moment for me to reflect on the specific characteristics and narratives of his work.

The Labour of Creativity

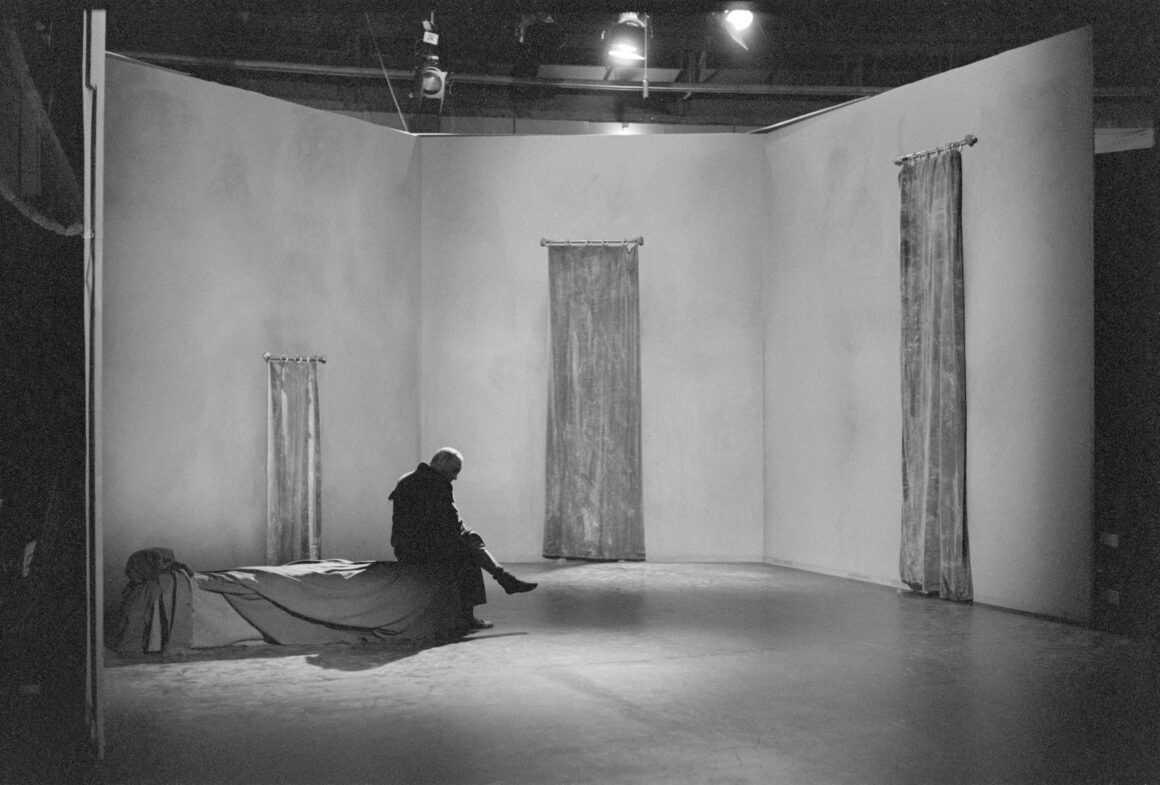

For decades, Michael’s home in Waterloo Road was his studio – or his studio was his home. There, I encountered a factory of creativity, a place of doers and makers. Michael alternated between the barely defined borders of his studio and living spaces, while his daughter, Aoife, and son, Oisin, worked separately on their own projects. Each had a private workspace, and everyone’s endeavour felt equally important; results and outcomes were shared and marvelled at collectively.

In my own experience, creative projects were not often validated and categorised as ‘labour’ at that time. Similarly, ‘labour’ was not seen as creative, and the uneven process of creative labour was rarely the subject of animated conversation between adult and child. I observed there, Michael’s view on the imagination as a sacred space for creativity, a territory worth defending, in which information and emotions collage into something greater than the sum of those parts.

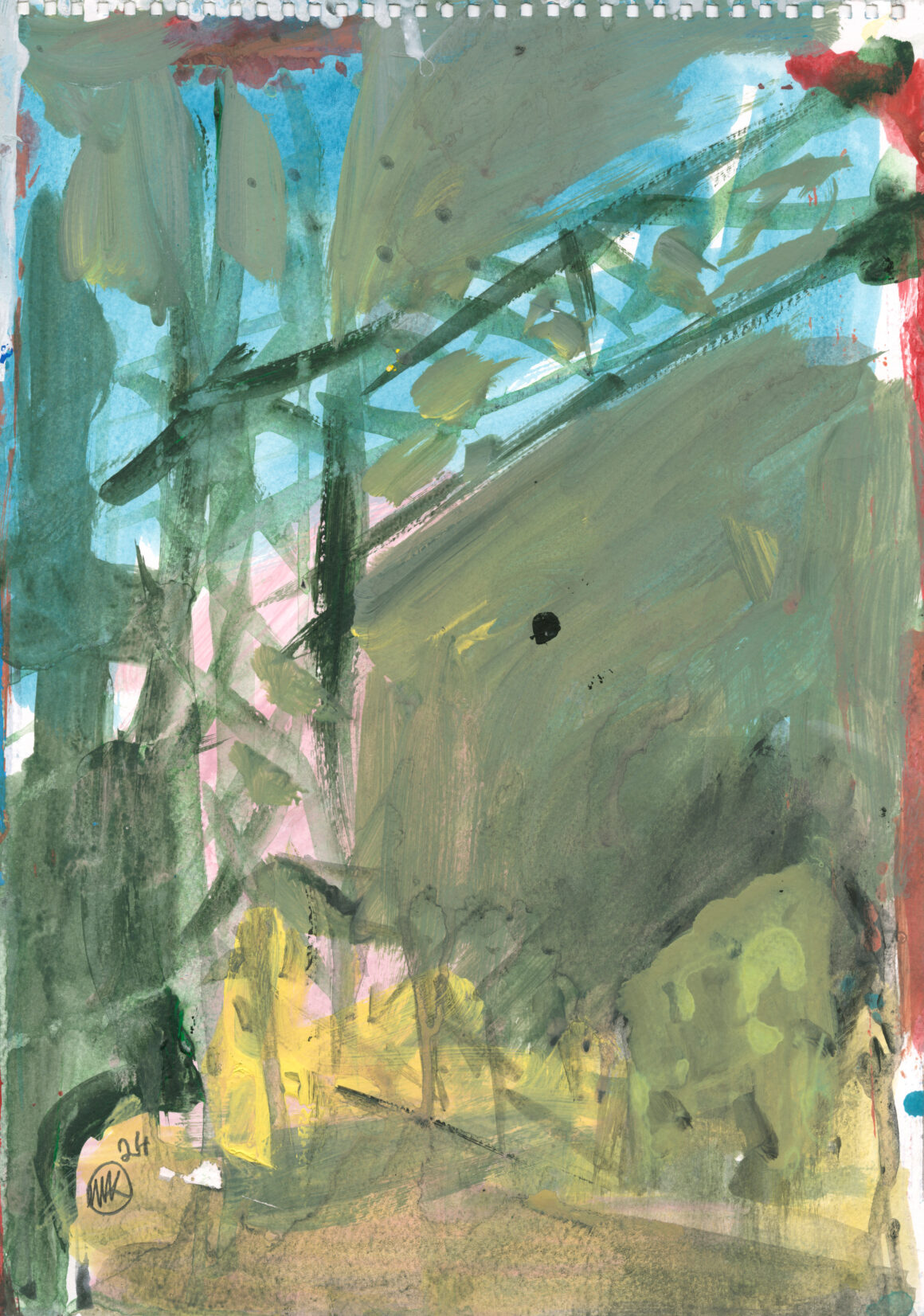

Michael works every day; he doesn’t wait for inspiration or any special circumstances. Michael wears work clothes, and he takes breaks for food, errands, periods of reading or news, but keeps these short. He’s intolerant of unscheduled interruptions. Michael has several projects on the go and is always starting new things. He assembles and manipulates materials and imagery; by sheer effort and trust in the process, his big bold paintings are laboriously coaxed into being.

Michael’s perspective and regard for his own labour explains his choice of subjects. Many monumental pieces portray the nobility, resilience and value of people engaged in physical labour and he celebrates mechanics, construction workers, stevedores, and factory workers as much as he does poets, gods and athletes.

Michael’s imagery is enriched by his reading, which he dismisses as “unscholarly and unsystematic,” although his autobiography, BLIND DOGS: A Personal History (Gandon Editions, 2023) chronicles an impressive reading list, already completed in his teens. Michael’s fluency in ancient Greek and Roman literature is an important context for his work – from the series ‘Agamemnon Felled’ to others exploring the fates of Icarus, Marsyas, Narcissus and more. He also published original poems informed by the classics: REALMS (1974) and IF IT’S TRUE (2005).

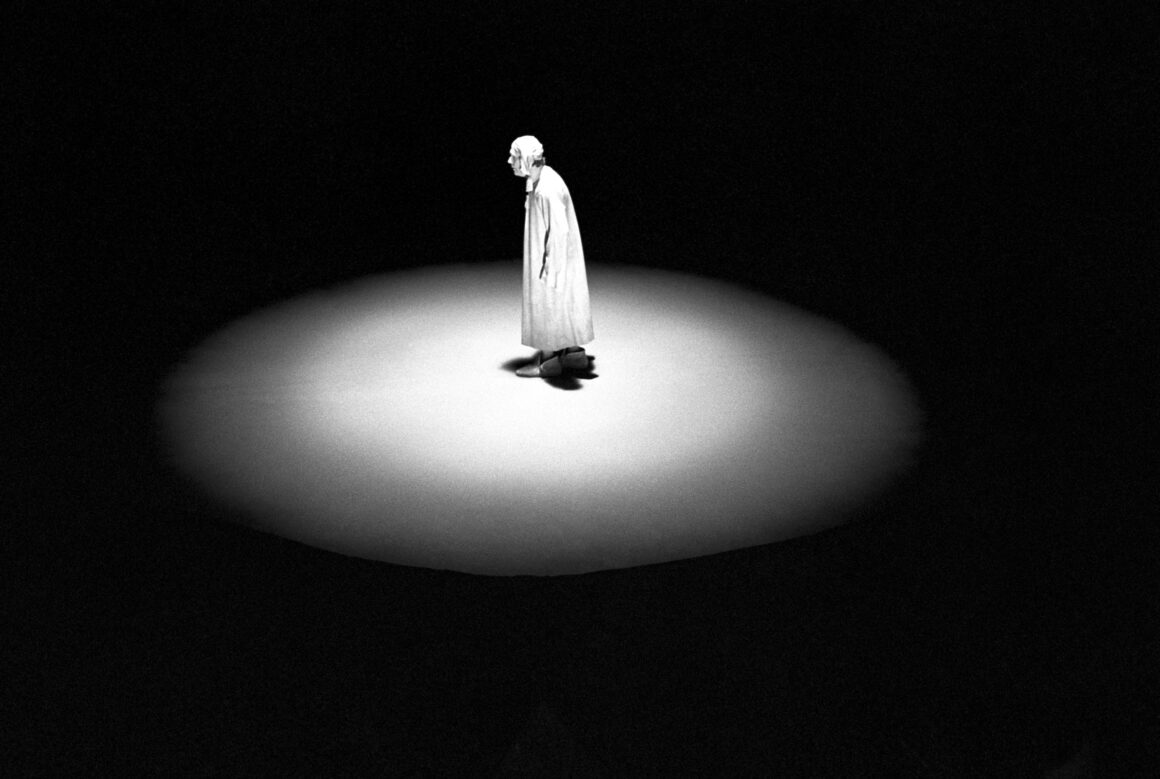

The Greeks saw their gods as utterly fallible, whose desires, ego and hubris are just like our own. Michael’s gods are full of struggle; they are sometimes depicted god-like, roaming the city, and sometimes appear in their ordinary human form. His interest in literature is balanced with an insatiable appetite for news, and both inform Michael’s understandings of human nature.

Places and People

Born in county Wicklow, Micheal wanted access to the bigger world of his imagination and, in many crucial ways, he found that in Dublin. The city is the backdrop for so many works that he has been described as a painter of urban spaces. Speaking with curator Seán Kissane in 2008, Michael said: “I don’t think I do urban landscapes as such. I do versions of an urban atmosphere, or something like that.”

Arriving in Dublin in his twenties, Michael interacted with writers Brendan Behan, Anthony Cronin and Patrick Kavanagh, painters James McKenna, Alice Hanratty, John Kelly, Charlie Cullen and Micheal Cullen, and several musicians, including Ronnie Drew and others in The Dubliners. Dublin was where Michael found his community of creatives and formed the “first inkling” of the possibility of life as a professional artist.

Michael also invested in building an ecosystem to support other artists. In the 70s he founded the sociopolitical magazine, Structure, commissioning original writing and art from young creatives. He established Independent Artists, an alternative to the rigid, prevailing gallery system, and was co-founder of Project Art Centre, a radical arts venue in Temple Bar. Michael was among the first members of Aosdána. So, while it’s true that Michael was drawn to Dublin as a place, it was the community, world vision, and sense that creatives could live collectively that kept him in the city.

Feminism and Tenderness

Michael often paints women. He is interested in the ways that women show up in the world and is aware of how the world shows up for women. His female subjects are mothers, gods, labourers, lovers, artists, survivors, students, and sex workers – each depiction, though complex, is wholly unambiguous. The women in his paintings squarely stare down or dismiss the viewer as they go about their business.

Michael never depicts women in fanciful poses; they assert themselves in the picture plane as they might assert themselves in a world that is often neither fair nor easy. He catalogues a malevolent cast of male characters circling these women – from the leering elders around the biblical Susanna to fiendish predators Michael recalls from twentieth-century Ireland. There is real tenderness in small drawings, watercolours and prints of women and girls that address violence, abuse, and cover-ups by church, school, and society. Many stories from this period recur in works throughout his career, never forgotten nor fully resolved.

When I started Rubicon Gallery, I was 21 years old, and a recent graduate. Michael was 55, a senior art college lecturer, and an established artist and cultural figure. I never felt less than Michael’s equal; business and creative directions were all up for discussion. I was invited to offer robust points of view, however contrary to his own, and together we negotiated solutions. Visual artists often won’t describe what they plan to do; meaning percolates through in the making. Sometimes it’s challenging to reduce what is done to plain words, because these things are often part of a longer unfinished body of work. Working with an artist over several years, I see that glimmers of insight emerge between the cracks and meaning coalesces over time. I am privileged for the time I spend with Michael in his studio, and for his personal humour and the stories that illuminate the work.

Josephine Kelliher works internationally as a Curator, Art Advisor and Cultural Strategist.

Michael Kane’s exhibition ‘Works on Paper’ runs at Taylor Galleries from 22 May to 21 June.

Michael’s work is also being shown in ‘Staying with the Trouble’ at IMMA (2 May – 21 September).