Exhibition Profile | On Television, Beckett

ANTONIA HELD REVIEWS A RECENT EXHIBITION AT WÜRTTEMBERGISCHER KUNSTVEREIN STUTTGART.

In a time when images and their contexts are consumed and forgotten in the blink of an eye, the question arises: Are we still capable of truly looking? As streaming services flood us with endless content, and algorithms dictate our viewing behaviour, reality becomes increasingly blurred. It is worth pausing and reflecting on an artist who not only utilised the medium of television but radically questioned it: Samuel Beckett.

The exhibition ‘On Television, Beckett’ at the Württembergischer Kunstverein Stuttgart (19 October 2024 – 12 January 2025) presented for the first time all seven television plays that Samuel Beckett produced between 1966 and 1985 for the South German Broadcasting Corporation (SDR, now SWR) in Stuttgart: He Joe (1966), Geister Trio (1977), … nur noch Gewölk … (1977), Quadrat I and II (1981), Nacht und Träume (1982), and Was Wo (1985).

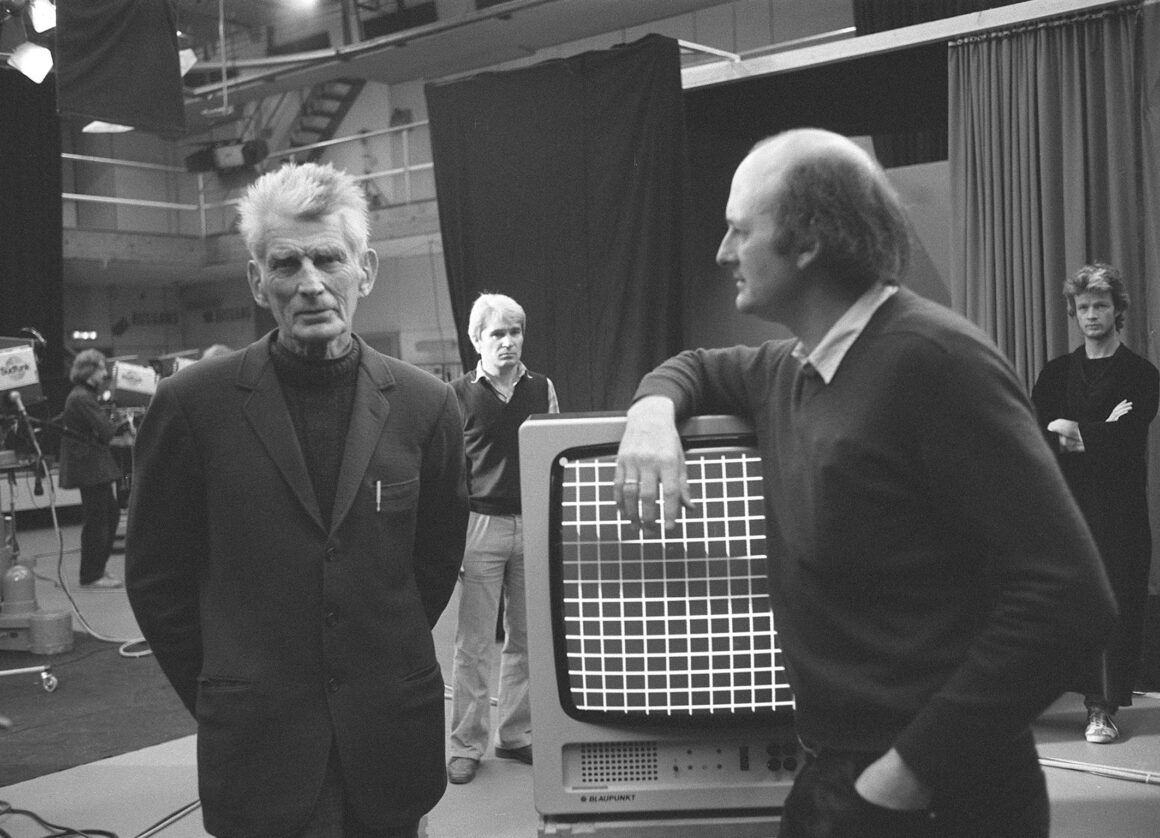

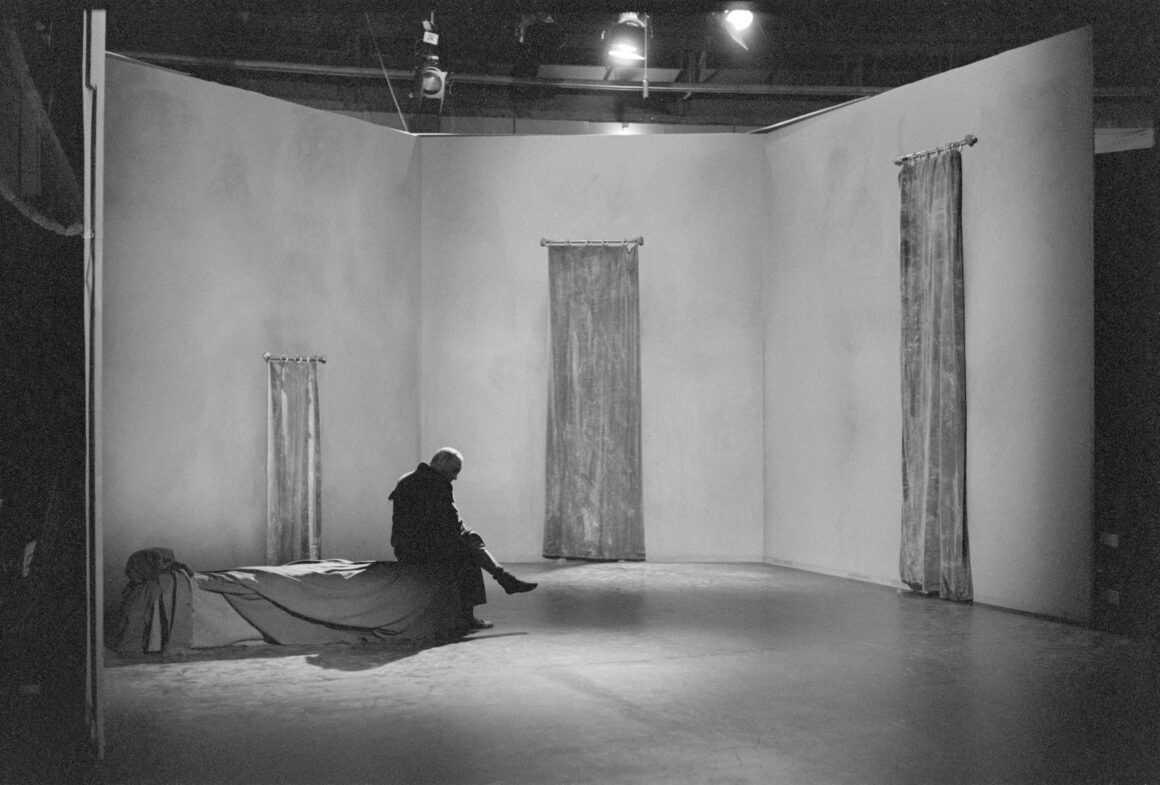

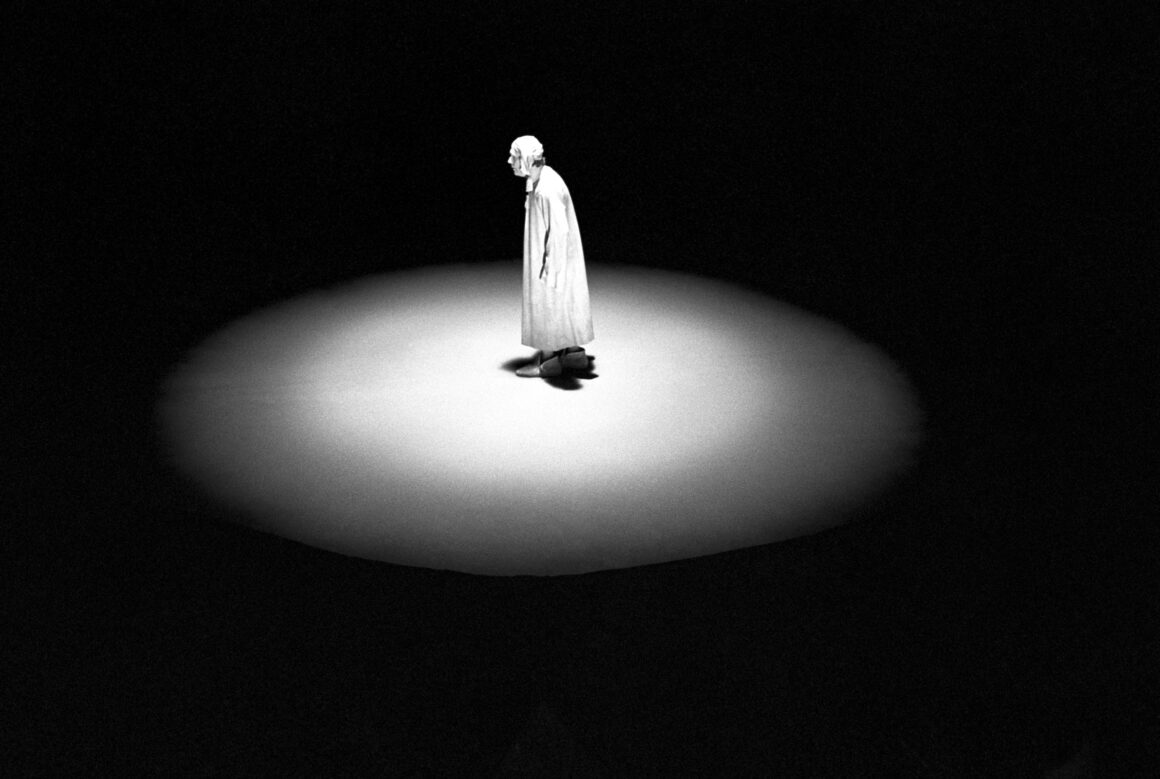

Production of Nacht und Träume, 1982; images © SWR / Hugo Jehle, courtesy of Württembergischer Kunstverein Stuttgart.

Curated by Gerard Byrne and Judith Wilkinson, the exhibition highlighted Beckett as a visual artist, portraying him as a precise designer of his works. Newly discovered photographs and production documents from the SWR Historical Archive, which document Beckett’s creative process over three decades, demonstrate that Beckett was not only an author but also deeply involved in the direction, visual composition, and editing of his films – pushing the boundaries of television as an artistic medium. His minimalist yet innovative aesthetic infused the medium with new depth and solidified his status as a visionary artist.

In the expansive exhibition space of the Kunstverein, the film works were projected within four cubes, which together formed an open, slightly offset fifth space, resembling a courtyard, the design of which borrows from Geistertrio. This was supplemented by two CRT monitors, one displaying Beckett’s film, Film (1965), the other a part of Alexander Kluge’s Deutschland im Herbst (1978), alongside a conversation with Otto Schily – lawyer for the far-left militant group, Red Army Faction (RAF) – and Eberhard Itzenplitz’s 1970 film, Bambule, which had originally been written by RAF member, Ulrike Meinhof, and therefore had for some time been banned from broadcast.

The exhibition vividly connected Beckett’s collaboration with SDR to the political history of Stuttgart. During the German Autumn of 1977, when the city was in the international spotlight, due to the actions of the RAF and the Stammheim trials, Geister Trio and … nur noch Gewölk … were created. Beckett’s themes – isolation, repetition, and the search for meaning – reflect the societal tensions of that time and touch on questions of freedom, control, and existence.

In Beckett’s television plays, he employed a radical reduction that questioned the very nature of the medium itself. That contemporary artists continue to engage with these works not only shows Beckett’s enduring relevance but also underscores the transformation and evolution of the media landscape since then. This was impressively addressed and expanded upon in the artists’ talks on 11 January.

The event included a conversation between Declan Clarke and Gerard Byrne about Clarke’s new film, If I Fall, Don’t Pick Me Up (2024), which had been shown to the audience the previous evening. Known for his cinematic investigations into modernity, conflict, and the hidden stories behind historical upheavals, Clarke brings a narrative sensitivity that can be compared to Beckett’s storytelling. While Beckett used television as a medium to abstract movements and question the structure of time, Clarke does something similar in his cinematic examinations of history and ideology.

Another engagement with Beckett’s ideas was found in the works of Doireann O’Malley, who merges virtual reality, artificial intelligence, and 3D technologies with cinematic and installation techniques. While Beckett explored television as a technological frontier, altering perceptions of body and space, O’Malley starts from a similar point, but in a world where machine intelligence and digital identities are already part of our daily lives. In their conversation with Judith Wilkinson, it became clear that their works address not only media transformations but also identity, gender, and perception, reflecting the changing narrative strategies in art. Beckett’s characters, often caught between dissolution and repetition, thus find a modern counterpart in O’Malley’s explorations of fluid identities and alternative states of consciousness.

The programme also addressed the artistic research projects of 2014 Turner Prize winner, Duncan Campbell, and the subsequent conversation between the artist and the curator bridged Beckett’s work with the present, opening up space for discussions. Campbell’s films, which deal with historical figures and political topics, explore the boundaries between documentary truth and narrative construction. This approach recalls Beckett’s staging of language and memory; where Beckett used forgetting, unreliability, and fragmentation as narrative strategies, Campbell questions the mechanisms by which history is constructed and passed down. Just as Beckett blended absurdity and seriousness, Campbell works with the tensions between documentary accuracy and narrative manipulation. In both, what appears as fact often remains a subjective and manipulable representation of reality.

‘On Television, Beckett’ made clear, through its combination of archival research, a comprehensive presentation of Beckett’s works, and conversations involving contemporary artistic reflections, that creative innovation often arises not from an abundance of possibilities, but from the conscious limitation to the essential – an idea more relevant than ever in times of information overload and manipulative media strategies. Perhaps herein lies answers to the yearning for authenticity in an increasingly simulated world. Beckett showed us the way – now it is up to us to truly look and continue his gaze.

Antonia Held is an art historian based in Stuttgart, Germany.